Gustavo's site

A compilation of my personal projects

What the hell is a tensor anyways?

Introduction

As I’m studying more and more differential geometry and general relativity (and being the noob that I am), I have to go back to this definition over and over again, so I thought that writing it down for good can help me (and hopefully others) get a quick refresher into what is a Tensor anyways.

Context first

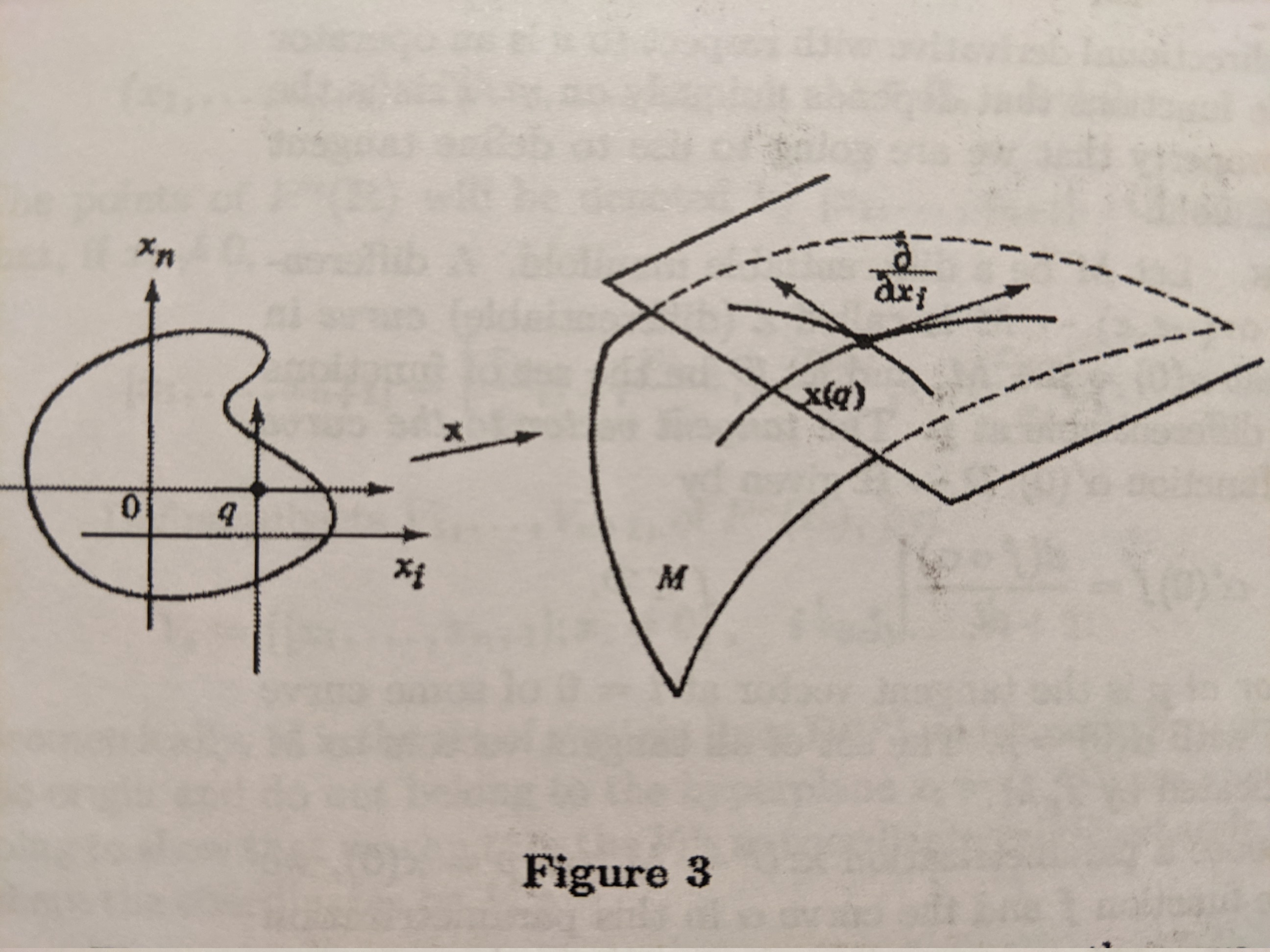

To get the definition going, we need to give some context first: We are on a manifold $M$, and for every point $p$ in this manifold we consider its tangent space $T_pM$ as the set of all tangent vectors on this point.

This is already tricky territory, because what we mean by “tangent vectors” is really directional derivatives that operate over smooth functions over the manifold. For example take a look at this definition of a tangent vector sneakely defined inside the definition of a differentiable curve in $M$ from do Carmo’s book:

The tangent vector to the curve $\alpha$ at $t=0$ is a function $\alpha’(0): \mathcal{D} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ given by

\[\label{eq:tangent_def} \alpha'(0) f = \frac{d(f \circ \alpha)}{dt}\vert_{t=0}\]A tangent vector at $p$ is the tangent vector at $t=0$ of some curve $\alpha:(-\epsilon, \epsilon) \rightarrow M$ with $\alpha(0) = p$.

*$\mathcal{D}$ is the set of all smooth functions $f$ over the manifold $M$.

If we flesh out this definition a little more by choosing a parametrization $x: U \rightarrow M$ at $p=x(0)$, we can express the function $f$ and the curve $\alpha$ in this parametrization by

\[\nonumber f\circ x(q) = f(x_1, \dots, x_n),\ \ q = (x_1,\dots,x_n) \in U\]and

\[x^{-1}\circ\alpha(t) = (x_1(t), \dots, x_n(t)).\]Therefore, restricting $f$ to $\alpha$, we can expand the definition of a tangent vector from above and obtain:

\[\nonumber \alpha'(0) f = \frac{d(f \circ \alpha)}{dt}\vert_{t=0} = \frac{d}{dt} f(x_1(t),\dots,x_n(t))\vert_{t=0}\\ = \sum\limits_{i=1}^{n} x_i'(0)(\frac{\partial f}{\partial x_i})\\ = \left(\sum\limits_{i=1}^{n} x_i'(0)(\frac{\partial}{\partial x_i})_0\right) f\]which we wrote purposefully to look like this whole thing is “acting” on the function $f$, kind of like a directional derivative! Right???! (It totally is a directional derivative when $M=\mathbb{R}^n$, but more on that some other time).

In other words, the vector $\alpha’(0)$ can be expressed in the parametrization $x$ by

\[\alpha'(0) = \sum\limits_{i=1}^{n} x_i'(0)(\frac{\partial}{\partial x_i})_0\]Note: As we saw above, the choice of a parametrization $x$ determines an associated basis $\{ (\frac{\partial}{\partial x_1})_0, \dots, (\frac{\partial}{\partial x_n})_0\}$ in $T_pM$, but always remember that each of those basis elements are little derivatives!

Ok, fiuuuu! That was a lot, but there you have the definition of a tangent vector, and the set of all tangent vectors is called $T_pM$ or sometimes $V_p$ (which we will use in the following section). Alright. What else we need?

Well we need to define/understand the dual space to $V_p$ , typically referred to as $V_p^*$. The dual space is the collection of linear maps over $V_p$ , i.e. functions

$f: V_p \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ so that $f$ is linear.

This might sound like a complicated space, but actually is just as simple (or complex haha) as $V_p$, because if you remember from linear algebra, the only scalar linear functions over vectors are exactly transposed vectors! (like for example the function $w(v)$

\(w(v) = [w_1,\dots,w_n] \left[ \begin{array}{c} v_1 \\ \dots \\ v_n \end{array} \right] \\\) \(= \sum\limits_i^n w_i v_i\))

So it shouldn’t be a surprise to hear that if for example $\{v_1,\dots,v_n\}$ is a basis of $V_p$, then $\{ v_1^\ast, \dots, v_n^\ast \}$ defined by

\[\nonumber v_i^*(v_j) = \delta^i_j\]is a basis for $V_p^\ast$! (just imagine the vector $v_i = [0,\dots, 1, \dots, 0]^T$ and its dual $ v_i^*=[0,\dots, 1, \dots, 0]$)

Ok, we have everything we need to define a tensor.

Tensor definition

A tensor $T$ of type $(k,l)$ over $V_p$ is a multilinear map

\[T: \underbrace{V_p^*\times\dots \times V_p^*}_{k \text{ times}} \times \underbrace{ V_p\times\dots\times V_p}_{l\text{ times}} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\]i.e. given $k$ dual vectors and $l$ ordinary vectors, $T$ produces a real number!

For example, lets consider a 1-1 tensor $T: V_p^* \times V_p \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$, one dual vector $w\in V_p^*$, and one ordinary vector $v\in V_p$ , then $T(w,v)$ is a scalar.

But this is way too abstract! To put things concretely we can write T using its “action” on the basis elements of $V_p$ and $V_p^*$ because it is a multilinear map. For example, let’s use the basis for $V_p$ that we described in the context section $\{(\frac{\partial}{\partial x_1})_0, \dots, (\frac{\partial}{\partial x_n})_0\}$, but rename it a bit for ease of reading and manipulation, say

\[e_i := \frac{\partial }{\partial x_i}\]so that we have a basis of vectors $\{e_1,\dots,e_n\}$, and their dual vectors $\{w^1,\dots,w^n\}$ , defined so that $w^i(e_j) = \delta^i_j$.

Notice that we are putting the index “i” on the bottom for tangent vectors, and on the top for dual vectors to differentiate them.

THIS IS IMPORTANT AND A HUGE SOURCE OF CONFUSION SOMETIMES #physicistscryinginthelibrary

So lets get applying T to these basis elements, for example the first elements: $T(w^1,e_1)$. This is a scalar, and lets call it

\[\nonumber T^1_1 := T(w^1,e_1)\]The same thing can be done with any pair $(w^i,\ e_j)$, so that we can describe T by the components

\[\nonumber T^i_j := T(w^i, e_j)\]This is going to be the typical way in which we will compute things with tensors; In their “components” or “coordinate” form, coefficients of an otherwise multilinear functional (sometimes to absurd levels like $T^{\alpha i j k\gamma}_{l s \beta}$ )

Conclusion

Hopefully this article would be a good reference to anyone (me in particular lol) for whenever the concept of “Tensor” gets confusing and we need a refresher.

We went over the basic definitions required to be able to define what is a Tensor. We learned about tangent vectors, the tangent space $T_pM$ (or $V_p$), its dual space $V_p^\ast$ and its inhabitants the dual vectors, and finally we defined what a Tensor is and how to describe it with a given set of coordinates.

So with all this in mind answer me this:

Is a vector … a tensor?

I’ll leave you to think about it, but the answer is in the comments.

Comments

Join the discussion for this article by clicking Here. Comments appear on this page instantly.

No comments found for this article.